Craftsmanship and fashion have always played a large part in the appeal of watches – and the history of timepieces has always shown it.

It is always difficult to draw a line between what is industry and what is craftsmanship – or even art. And quality watches very often dwell in this middle world of imperceptibly blurred boundaries, spanning the three realms.

After all, what invisible wall separates art from industry – assuming that luxury watchmaking is an art? Probably, it is the same limit, impalpable but present, that divides pret a porter from haute couture in fashion. And if you’re not used to this terminology, we’re talking about fashion houses’ “ready-to-wear” garments compared with bespoke clothes.

Both will bear the same label – for example, Giorgio Armani – but the final result will be completely different. And you won’t be aware of the extent of the difference until you’ve tried both. In a nutshell, a bespoke suit is cut on our exact body, while a ready-to-wear suit is intended for a typical size and then has to be adjusted to conform to our body – unless we are among the lucky few to be built like what fashion designers call “a perfect size.”

Watches until the 1870s were one-of-a-kind pieces

While we’re racking our brains over this question, we need to refer back to the history of watchmaking and discover that the watch has historically had much more to do with clothes than it has to do with cars. In fact, out of a watchmaking history that spans more than 500 years, only 20% of then – temporally speaking – relies on perfectly reproducible watches. The first watches, although produced in “series” – or at least, with very similar characteristics, in reality, have always been unique pieces, difficult to compare even if visually identical.

This goes back to the characteristics of watchmaking, which, rather than an industry, has always been craftsmanship. Or at least, it always was so, until two fateful dates, which changed the course of history to make watches affordable, if not to everyone, to many.

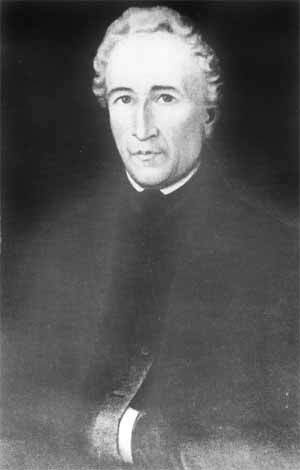

The genius of Lépine

Jean Antoine Lépine, whose name is also reported as l’Epine, was a Parisian watchmaker who lived in the mid-eighteenth century and had made a career working at the court of the Kings of France. So much so that he had married the his mentor’s daughter – the King’s watchmaker, Caron – as was often the case at the time, becoming his heir to the Royal Appointment.

But more than a simple profiteer, our friend Lépine was a notable professional who worked hard to improve the quality of French watchmaking, which was a bit like the “poor cousin” of the market leader back then: England. In fact – and not many people are aware of this – for a hundred years, England was the most important country for the production of watches.

And this was caused by a concomitance of factors, which included the presence of great inventors and technicians and an enviable strategic condition caused by the government’s spasmodic attention to encourage precision watchmaking. Without wasting too much time, here we have historical proof that investment in R&D is critical to ensure competitive advantage for key industries.

Lépine, along with other watchmakers of the time, such as Leroy and especially Ferdinand Berthoud, would bring back to France the leadership of the watchmaking industry through their skill and insights. In fact, Lépine, around 1765, developed his famous caliber concept – a standard movement that could be mounted inside watches of the same type. And if this seems trivial to us today, we must consider that it was instead a revolutionary concept in Lépine’s time and long after.

The caliber that destroyed English watchmaking

Lépine’s real intuition was to simplify the movement of English clocks, which were based on the verge fusée, or an escapement based on a mechanism that hailed from the timepieces of the 1500s. One of the limitations of this mechanism was its design, which needed two separate horizontal planes: the winding on the “ground floor” and the balance oscillated on the “second floor.” This made British-made clocks thicker and more complicated to build because of the difficulty of perfectly centering the mechanisms on the two levels.

Lépine introduced the virgule escapement, similar to the cylinder escapement, which had the virtue of operating on one plane only, making French watches much thinner, and allowed French watchmaking to become dominant worldwide. In a letter, the American President George Washington asked to Gouvernor Morris, who was in Paris, for a simple, gold watch of good quality, similar to the “big, slender” one that Thomas Jefferson had purchased on behalf of James Madison. As we can see, even the greats of history had their little vanities. And human taste creates and destroys even the most solid industries.

Replaceable parts, the coup de grace to craftsmanship

Despite the fundamental development of the caliber concept, watches continued to be made in workshops with limited production capacity, and the gears had to be adapted and calibrated in each timepiece. The result was that it was uncommon for even two identical clocks to swap parts: they were similar machines but imperceptibly different.

This situation went on as the industrial revolution progressed. Until around 1830, one of the most important contributions of American watchmaking took off: the concept of “replaceable parts.” Precision mechanics was that important branch of industry pushing the war machine – and so, to ensure the production and maintenance of armaments such as rifles and pistols, armorers began to introduce this fundamental concept, which would become the primary axiom of the mass output of every sort of complex tools – including watches.

The Waltham Watch Company, founded in 1850 by Aaron Dennison, was one of the first companies to work with mass production. This allowed for sufficiently accurate and less expensive watches than their Swiss equivalents. And this revolutionary concept was taken up by other innovators, such as Florentine Ariosto Jones, who had worked as a director in Waltham, and settled in Switzerland from America to build watches based on this system. The company he founded was called International Watch Company – or IWC.

In order of time, the last of the industrialism pioneers was Georg Friedrich Roskopf, who simplified the watch mechanism to produce his “Proletarian Watch,” industrially mass-produced at low cost – two weeks’ pay for the average worker. Around 1870, after a significant boycott by the traditional Swiss industry, which considered him a sort of “heretic,” Roskopf timepieces were sold in millions worldwide: mass watch production had begun and would continue to this day.

The two markets, brand, and luxury

From here, two parallel markets developed, in some cases merging into one another. First, manufacturers of standard movements, the ebauches, began to work to supply companies that produced watches industrially or semi-industrially, giving rise to the phenomenon of Etablissage, i.e., companies that manufactured watches by combining elements from different suppliers. In contrast, the term Manufacture is used to define manufacturers that did all the work in-house.

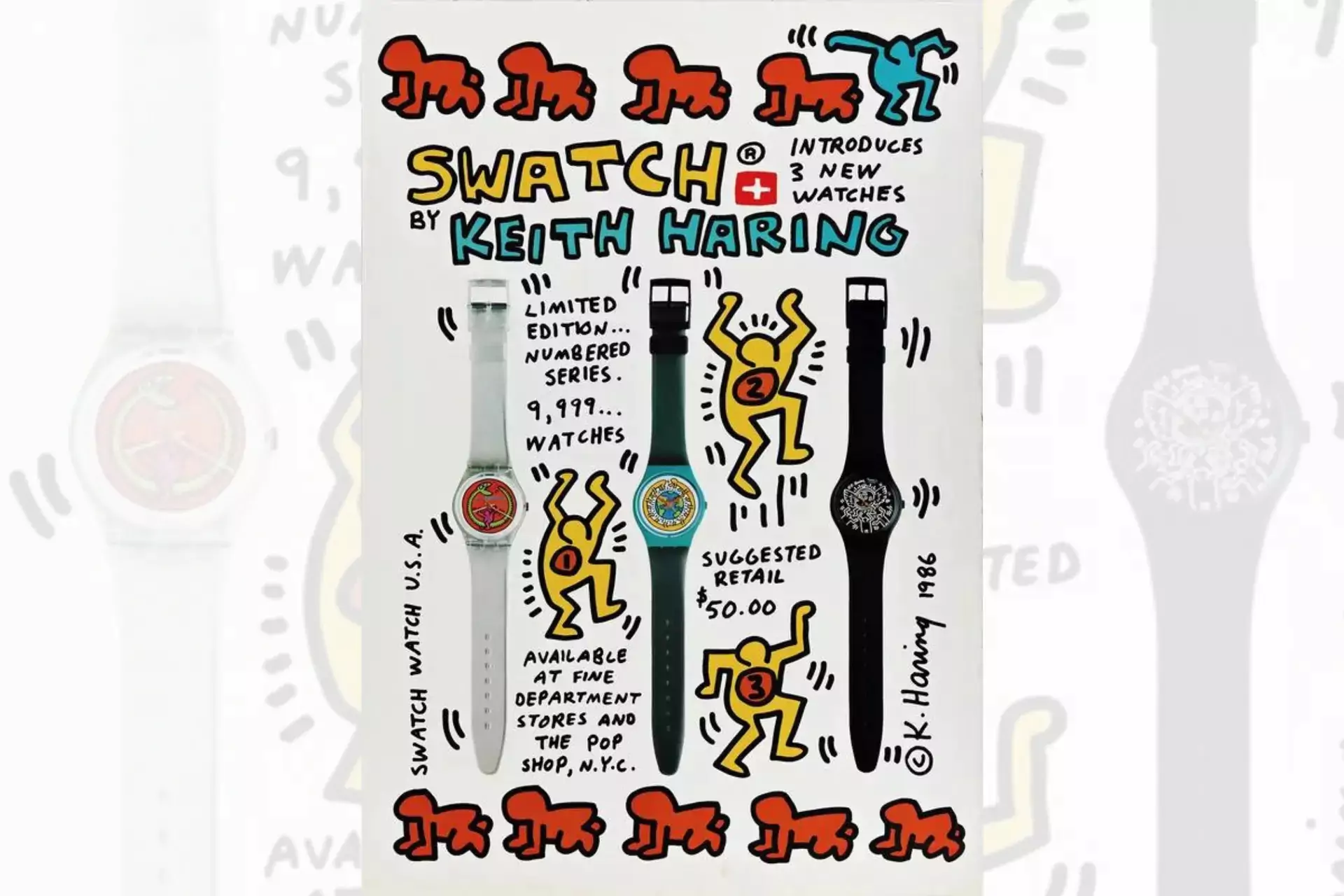

The tremendous industrial development that took place after the Second World War, and the upheavals of the Quartz Crisis, led to the formation of some industrial mega-groups, such as the Swatch group, which by now has assumed a dominant position in the Swiss watchmaking market, integrating within itself every type of production, from movements to brands, components, and lubricating oils.

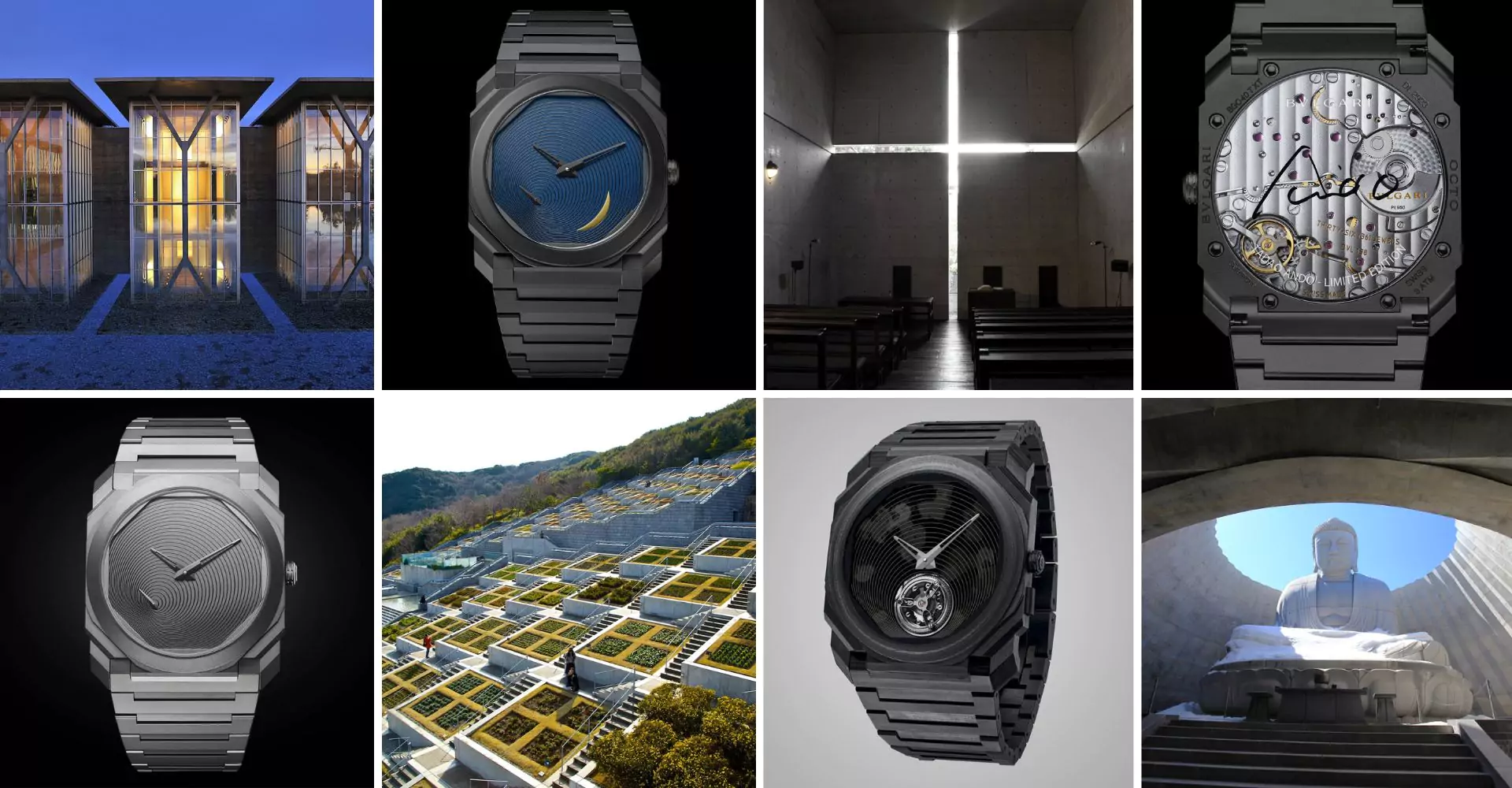

But aside from this market of “brands,” there continues to be a market of luxury watchmaking, which still follows traditional methods, enriching them with modern technical discoveries, and produces the most horologically exciting pieces – and in many cases, the two realities are closely intertwined.

For example, Vacheron Constantin, the oldest existing watchmaking brand in continuous operation since its founding, has an “industrial” production of high-end watches and an “artisanal” production of made-to-order pieces produced by its specific department called Les Cabinotiers. Unique collector’s timepieces are made at the request of clients, who have them constructed according to their wishes, precisely as if they were a made-to-measure suit.

And similarly operate the modern master watchmakers, such as Roger Smith. He still works on machine tools dating back to 1800, inherited from his master and mentor, the inventor of the coaxial escapement, George Daniels, in his workshop on the Isle of Man that produces 12 watches a year. Not one more.

Between the extremes of massified luxury – let’s remember that Rolex produces about a million watches a year – and these cases of handcrafted production bordering on horology art, there is a variety of intermediate situations that make it impossible to come up with a proper standard on what is industry, workshop, craft, and art. Some have called watches “Art in Motion” – and that’s a definition we really like (even if Calder would probably be dubious).

Even though there is neither art nor craftsmanship in many watch productions, and they are derived mainly from mechanical assembly, there is always a human intervention that completes them and takes them to a different level of belonging and participation.